Voice of an Ancestor

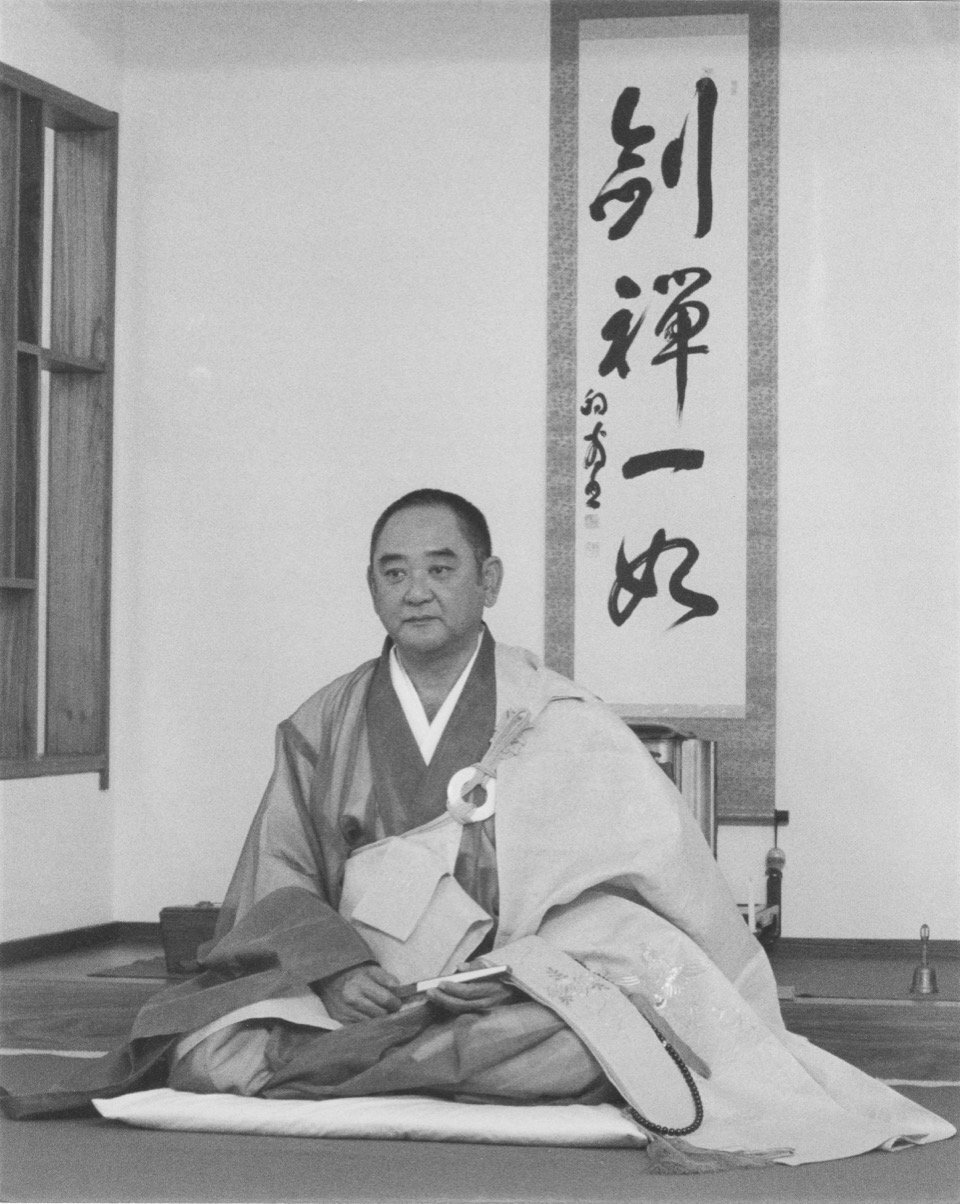

That title comes out of an email from Ellen McKenzie, saying that she realizes that our new Chosei Zen publication series – Tanouye Roshi Teaches – allows her to hear “the voice of an ancestor,” her Zen teacher’s teacher. Though Tanouye Roshi died in 2003, his teaching is timeless. In a growing series of publications we are presenting edited versions of talks that Tanouye Roshi gave more than forty years ago in various settings, some of them quite informal while others are formal teisho given during sesshin.

There was a precursor to this publication series, namely A Warrior Becomes a Monk, published in 2022. That monk was a robust character in the great medieval Chinese saga called The Water Margin. The story of that monk, Sagacious Lu, is one of the best introductions to the character of Tanouye Roshi for people who don’t know Zen Buddhism. That publication contains a retelling of the monk’s origin story but in the Afterword we shift to talking about some of the figures, both historical and mythical, that Tanouye Roshi drew upon when teaching, time after time.

The next publication, and the first in the Tanouye Roshi Teaches series, is Five Lessons on Zen Training. Four of these lessons are transcripts of a range of talks given on the US Mainland, starting with a long presentation on the relationship between Zen and the martial arts, and ending with a wonderfully clear instruction on how to use your breath and posture for koan training.

The second publication contains Tanouye Roshi’s teisho on Hakuin’s Zazen Wasan, the poem written in praise of the merits of zazen and chanted nightly during sesshin. Hakuin alludes to several iconic stories from Buddhist sutras, so Tanouye Roshi fleshes those stories out for his listeners.

The third publication in the series is currently in preparation: The Art of War: A Dialogue Between a Zen Master and Sun Tzu. This work comes out of the first half of a multi-day seminar that Tanouye Roshi presented to several employees of a savings and loan company based in Honolulu. He interprets the first six chapters of The Art of War from a unique perspective: that of a Zen master, a martial artist, and someone who taught himself to read Chinese by studying the characters in the original text.

So how closely are we giving Ellen the chance to hear the voice of her teacher’s teacher? As you know there is a traditional phrase that starts most every sutra, a written work presented as if they are transcripts of talks by the Buddha. The phrase is “Thus I have heard.” If you think about it, this is not the same as “This is what the Buddha said.” By writing down what you heard some say you are going through a sophisticated but mostly unconscious neurological process to render speech as meaningful writing. Another way to say this is:

A word spoken carries feeling; a word written carries meaning.

I say this because my role as editor of this publication series has been to convey “thus I have heard.” You might like to think you are reading Tanouye Roshi’s words as spoken, but you are really reading words as I “heard” them when going through transcripts of widely varying quality.

But that hearing is also literal; I am easily hearing his voice while I am editing. There becomes a dance between the feeling of the spoken word and the meaning of the written work – one that all are invited to join.