Pilgrimage As Practice

I only went out for a walk and finally concluded to stay out until sundown, for going out, I found, was really going in.

John Muir

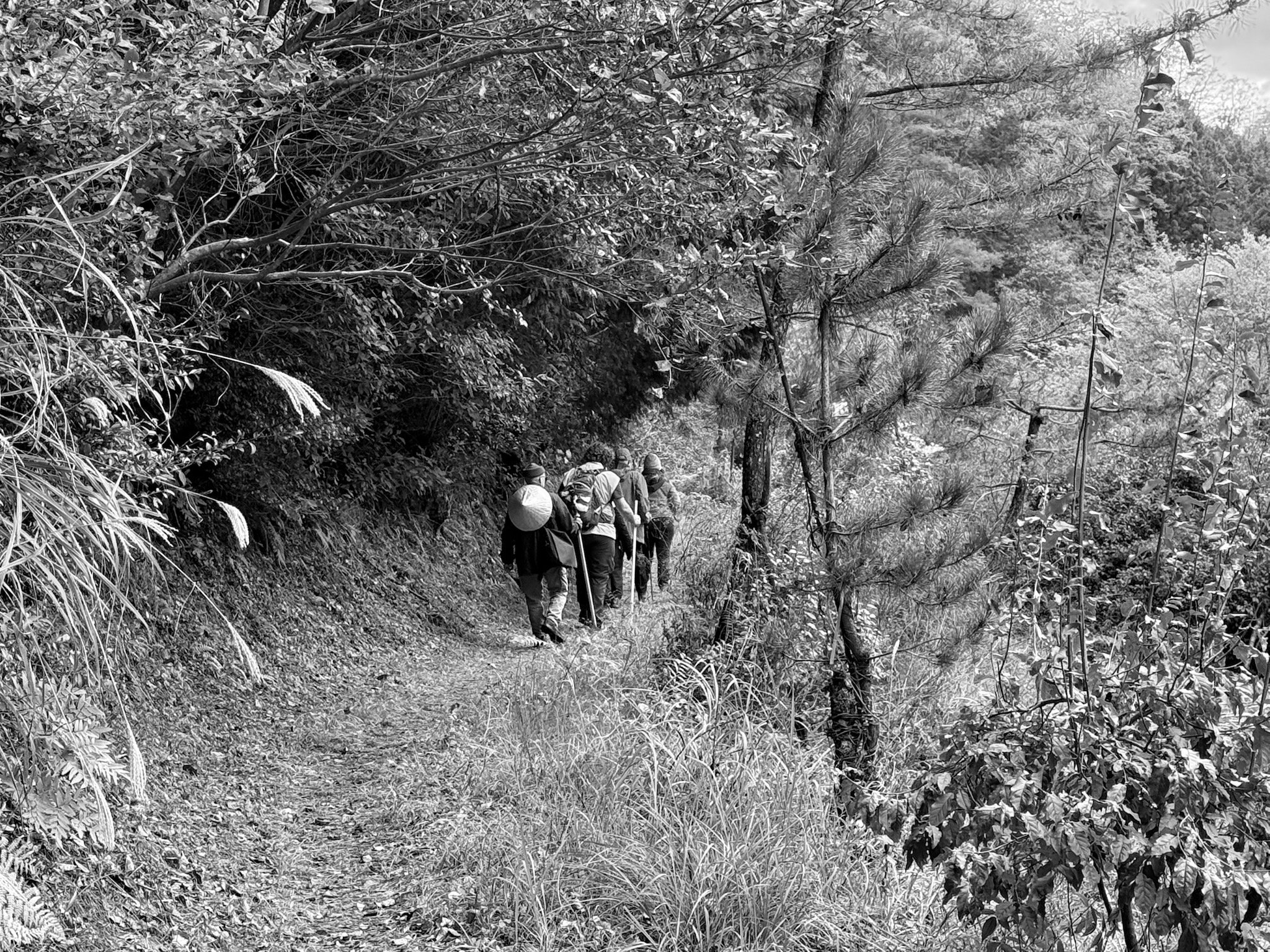

I recently returned from a pilgrimage to Japan, walking a section of the Shikoku Pilgrimage with Gordon Greene Roshi and Pat Greene Roshi, Pittelli Sensei, and Bethany and Eric Howlett. The trip was planned by Greene Roshi to revisit a section of a journey he first made over 50 years ago, walking the 1200 km circuit of Shikoku Island, a path that visits 88 Buddhist temples established over the past thousand years. I think I was invited, at least partly, due to my lifelong experience of walking, mostly wilderness hiking in the the American West. But in recent years, as my concern for our troubled times has grown, I have taken up the pilgrimage. A pilgrimage is a walk of unusual time and distance. A physical and mental and ultimately spiritual journey across an exterior and interior landscape one traverses carrying some difficulty, loss, wish, or question. Consciously or unconsciously.

Pilgrim comes from the Latin, “perigrinus”— to be away from one’s land, home. That is a common feeling today, for humans across the world. To be away from one’s land, one’s home. That separation can be physical, but it can be psychological, emotional, political, or spiritual. A pilgrim is different than a refugee, who is someone who has lost their home, forced to leave. A pilgrim chooses to leave home in order learn something, or find an answer, to grow, or to heal. The pilgrim leaves, to be able to return, transformed.

Caminate, no hay camino. Say hace la camino al andar. Al andar say hace la camino.

Traveler, there is no path. You make the path by walking. By walking you make the path.

Spanish Poet Antonio Machado

In Greene Roshi’s 2025 New Year’s message he wrote of sonomama, the essential “isness” of a thing. Walking, for humans, how and why we walk, is part of our essential “isness”. Walking is in our DNA, in the structure of our bodies and in the history and culture we have created since we first walked out of East Africa a million years ago, now to every point on the globe. We are made to walk. And what happens as we place one foot in front of the other over and over and over again, walking across plains and mountains, through villages and cities, alone and in the company of others, at three miles an hour or so, towards some target destination, is that time slows down and some essential peacefulness and clarity emerges. Our senses are heightened. The ground beneath us tells us we belong here. And as we walk on, the expectations or limitations or fears we have been carrying begin to slowly fall away, allowing the answer or awakening we have been seeking to rise up from the path or from the far horizon and meet us.

Pilgrimage by its nature is a step into the unknown, mystery, the hidden. A response to some inner calling that is made manifest and revealed by walking toward it. It shares that nature with poetry, which is also the attempt to understand or express something unknown, unclear, seemingly out of reach. Poetry through language. Pilgrimage through walking. Both are “just beyond yourself,” as poet David Whyte would say.

Just beyond yourself, it’s where you need to be. Half a step into self forgetting, and the rest restored by what you’ll meet.

Last Spring I completed the 539-mile Camino de Santiago section from southern France to Finisterre, Spain (the end of the world). After 36 days walking, I broke down crying, tears of gratitude, as I walked up that final hill in the evening air and stood on the edge of the rim overlooking the Atlantic Ocean as the sun began to slowly fall toward the western horizon, as pilgrims had done for a thousand years before me, and as the pagan Celts and their ancestors had surely done for millennia before then. I was in the company of multitudes and all creation. As St. Augustine said, Solvitur Ambulando. It is solved by walking.